In the process of the decline of the Golden Horde, the strengthening of the kingdoms of Hungary and Poland, as well as the beginning of the formation of the Moldavian principality (1359), the area where the town of Tigin would later appear on maps and in written sources was included in the zone of influence of the Yamboluk horde. The power of this powerful horde extended over a significant territory on the right bank of the Dniester, up to the borders of Lithuania, Poland and Hungary. From the left bank, the territory was controlled by the yurts of Khachibey (Hadzhibey), and from the south by the yurts of Kutlubugi. The same uluses also controlled the crossing of the Dniester in the area of present-day Bendery.

In addition, in the same region, in sufficient proximity to our city on the Botna River (a tributary of the Dniester), there was an unnamed Golden Horde city, and on the Reut River, the city of the Mongols Sheh-al-Dzhedid (New City).

In different documents, written sources and maps, the name of the city will vary somewhat: Tyagyanyakyach, Tyagyanyakyachu, Tyagyanyakachiu (Tyaginya-na-kyachu), Tyagin, Tigina, Tigin, Tekin, Tungati, Tishno. On Polish, Lithuanian and other European maps the name of the city is inscribed as: Tehinia, Tehyna, Teghinea, Tehin, Thehinia, Tekin. It is clear that the root of this toponym is the same.

City names are always historical and do not just appear. As a rule, they testify to the origin of cities at the crossing points, the routes of trade routes, the initial occupation of the population, etc.

In scientific circles, there are two versions of the origin of the name of the city. One version is Slavic, according to which the name of the city comes from the Slavic word “pull”, “pull”, “thin”, meaning the process of pulling ships with cargo through the existing crossing. The second version is Tatar, according to which the name of the city is associated with the Turkic term "tegin", "teggin", which is translated as "prince", "prince", and also denoting the highest dignity and special honor. This term is also known in Tuva, far from us, where the name of Kul-tegin is carved on tombstones associated with the history of the Turkic Khaganate of the 8th century. The same designation is found in Chinese chronicles and among the Oghuz tribes of the time of Genghis Khan and was widespread both in Altai and in Central Asia. It is also possible to associate this toponym with the Oghuz tribe of the Tekins, close to the Yases (Alans).

Some researchers who advocate the Turkic version of the city's name translate its meaning as "trough", "cup", "frying pan" - from "tagan", "tigan", which, in their opinion, expressed the originality of the area, the steep bend of the Dniester.

The oldest initial mention of the city as Tyagyanyakechu, Tiginyakyachu the most difficult to decipher. A number of scientists believe that the expression "kechu", "kyach" is nothing more than the Old Slavonic expression "kyashcha", i.e. "house", "tent", "hut". Others believe that the term "kyachi", "kichi" means nothing more than the designation of shallow water, a crossing that was common at that time. This term was also widely used in the Romanian lands, especially when designating shallows on the major rivers of the region.

Although there are similar words that also have Turkic roots, which may indicate that over time the Old Slavonic name of the city has changed and transformed into a more convenient pronunciation for the population living here.

It should be noted that the Tatars gave names to many settlements of Bessarabia, including the capital of Moldova - Chisinau, "kishla" - a wintering place, a farm and "know" - a new one.

There is also a more original version of the origin of the name of the city, the so-called Genoese, originating from the corrupted Latin expression te Hennae (To you Genoa).

It is difficult to say whether there was any large city or even a fortress on the site of the current Bendery before the arrival of the Turks. The versions of the origin of the fortress will be discussed in another publication.

For the first time in international Russian and European sources, in particular in the Russian guidebook and on maps, Tigin appears only in the middle of the 16th century, under the name Teginnya. On the map of Europe by G. Reichersdorf, dated 1550, such a settlement as Tehynie appears.

Important documents for historians of that time, which described the existing cities and settlements, including those in our region, were:

- “List of Russian cities far and near” of the end of the 14th century, where Russian, Bulgarian, Volosh and Polish cities are described in detail;

- Notes of the "Bavarian squire" John Schiltberger from 1427;

- Memoirs of the diplomat Gilbert de Lannoy (a trip to the Crimea in 1412).

- The treatise "On the Two Sarmatians" by Matvey Mekhovsky from 1517 and there are no descriptions of the city in the documents of the Austrian diplomat Sigismund Herberstein from 1517 to 1552, who visited Hungary, Poland and Russia nine times from 1517 to 1552.

Tigina is not mentioned in these documents.

Therefore, the sources of the Moldavian Principality are so important, where the toponym Tighina, although rarely, already appears in official documents, which indicates the involvement of the town in the economic and political activities of the Moldavian state. In the gospodar charters, the city was mentioned in 1408 as Tyagyanyakyachu, in 1452 as Tighina, in 1456 as Tyagyanyakyach, in 1460 again as Tighina. Since that time, the toponym Tigina has finally been assigned to the name of the city.

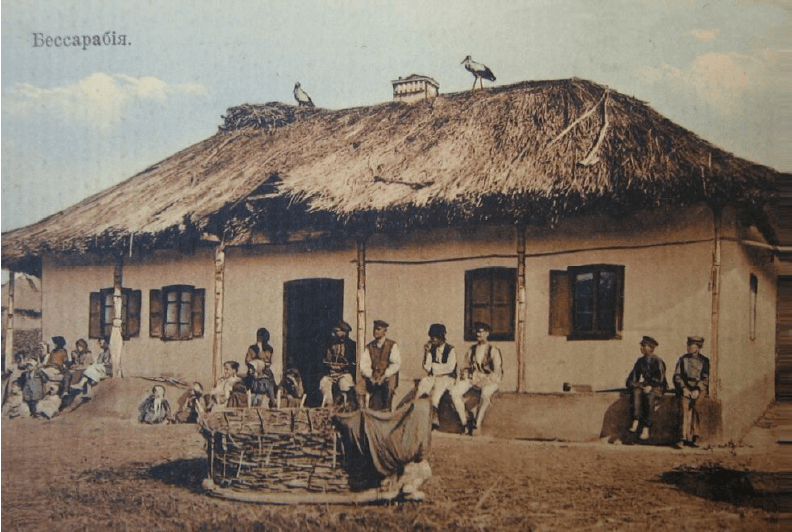

The process of self-identification of the Moldovans was quite long, which survived the stage of separating themselves first into a separate branch of the Volohs, and then into an independent nationality. It ended in the XIII - early XIV centuries. The Moldavians, as a nation, turned into a separate branch in the northern part of the Carpatho-Dniester lands as a result of the assimilation of the Romanesque group of Volohs with the Rusyn Slavs living here. This happened mainly in the areas of the Bistrita, Moldova and Suceava rivers. Unlike future Romanians, during the formation of the Moldavian nationality, the Slavic influence turned out to be more significant.

In the XIV century, the Golden Horde fell into complete decline, the lands of Moldova, located on the outskirts of this empire, were the first to free themselves from the Tatar-Mongol yoke. Hungary, having defeated the Mongol army in the 40s of this century, took control of the entire western part of Moldavia. In 1359, as a result of an uprising against the Hungarian kings, an independent Moldavian principality arose, headed by Bogdan, who was previously a Wallachian governor. The Moldavian principality arose in the basin of the Moldova River, and therefore the country began to be called Moldavia. Soon the southeastern part between the Prut and the Dniester was also liberated from the Tatars. By 1400, Belgorod was also included in the principality. The city of Tigina ended up in the east of the principality, the border of which ran along the Dniester. In Turkish documents, the new principality began to be called Bogdaniya, in Russian - Volosh land, sometimes - Lesser Wallachia. In addition, Europeans, as well as Turks and Russians, distinguished Volokhov and Moldavians, calling the former black Volochs (Vlachs), the latter white.

At the time of the creation of the state, and even afterwards, nevertheless, a significant eastern part of the country actually remained under the rule of the Tatars. The military historian A. Zashchuk writes about this in his work devoted to the military review of Bessarabia, published in 1862: “At least, Bessarabia never constituted an independent and even a common region. It contained three that were previously quite separate. 1) Most of the current Khotinsky district was Raya, i.e. a Christian province of the Moldavian state, exclusively belonging to the Turks. This was a border country, where the Poles waged an eternal war with the Turks and Moldovans for Bukovina. 2) The current counties: Yassky, Soroksky, Orgeevsky, Kishinevsky up to the Troyanov shaft were nothing more than the Zaprutskaya part of Moldavia. 3) Finally Budjak, i.e. the current districts of Akkerman and Bendery were from time immemorial the steppe, the inhabitants of which never changed their nomadic way of life. The last of the tribes wandering here were the Nogais, subject to the Crimean Khan and the Ottoman port.

Legally, the young Moldavian principality also did not remain independent for long. Already at the beginning of the 15th century, Turkey began to expand into this and neighboring regions, the appetites of which the neighbors will soon have to evaluate. In 1415, the ruler of Wallachia, Mircea the Old, began to pay tribute to Turkey in 3,000 gold pieces, recognizing his vassalage to the Ottomans. In 1420, the Turkish fleet attacked the Moldavian Belgorod (Chetate Alba) and attempts to capture Chilia that same year. Unlike Wallachia, the Moldavian Principality begins to pay tribute to Turkey only in 1456, in the amount of 2000 gold coins, during the period when Moldova was weakened by internecine wars (1430-1450). This so-called harach meant that in exchange for the payment of tribute, Turkey provided these areas with almost complete independence. Even in the heyday of the Moldavian principality, it is legally a vassal of either Poland, or Hungary or Turkey. And sometimes several states at the same time.

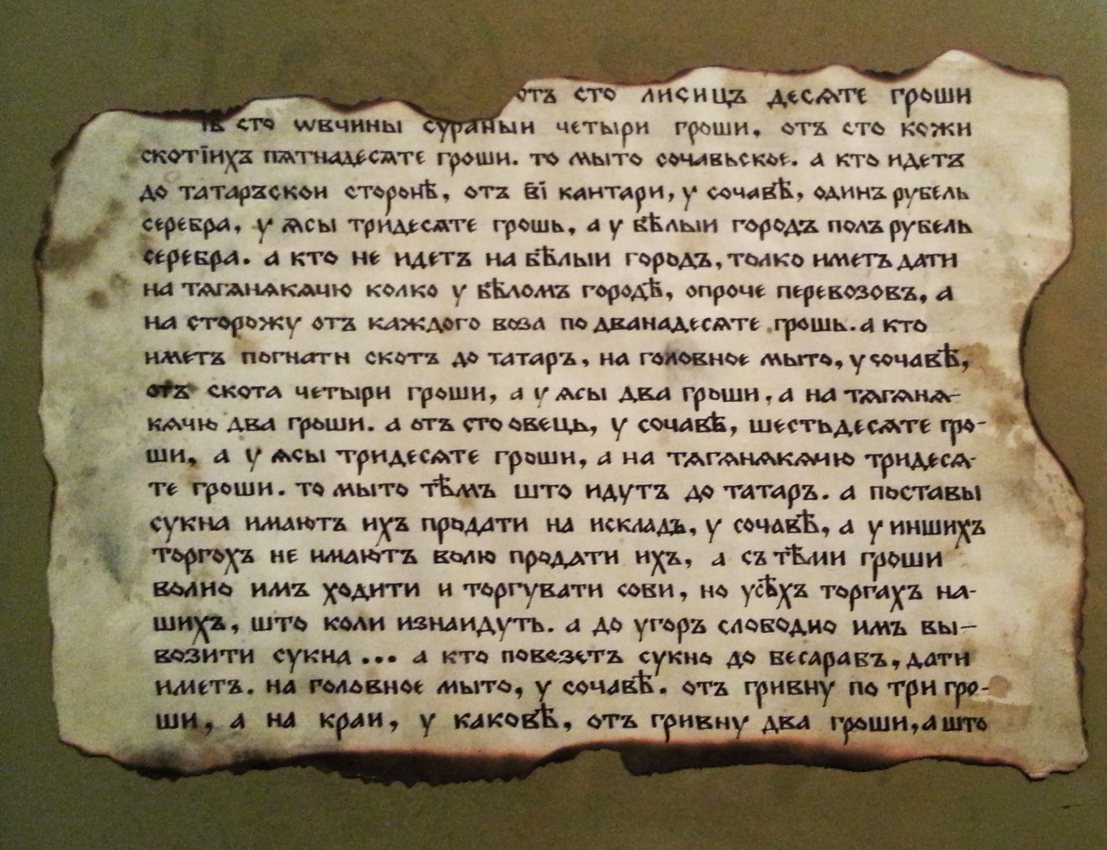

In historiography, the age of the city is usually determined by written sources. Therefore, the age of the city of Bendery (Tigina) is calculated from October 8, 1408, it was on this day that the Moldavian ruler Alexander the Good signed and sealed the letter with his seal. It was in this charter that for the first time, among other cities, our city was mentioned under the name Tyagyanyakyachu. The letter, in which trade privileges were granted to Lvov merchants, is in itself very informative and therefore priceless. The charter established duties on the main types of goods that were levied in different cities from local residents and foreigners. The size of the duty on goods in such cities as Iasi, Belgorod and Tyagyanyakyach was the same, which still cannot speak of approximately the same level of trade in these cities, with regards to Tyagyanyakyach, we are most likely talking about a large flow of goods through customs and the crossing of this settlement. The letter specifically highlights: "... and who goes to the Tatar side" in Tyagyanyakyach was obliged, in addition to duties for transported goods, to pay additionally and transport them across the Dniester River. In addition to these taxes, it follows from the text of the letter that one more type of tax had to be paid: “... and for the gatehouse from each wagon for twenty pennies ", i.e. pay for the gatehouse. Here we are apparently talking about paying a tax on the maintenance of the protection of the existing crossing. In some Western documents, where Tigin is referred to, the term "Straja" is also mentioned. In Tighina, it can be stated with full confidence that there was a permanent stationary post protecting the crossing, where the children of the Moldavian boyars and local residents served.

It is known that during the heyday of the Moldavian Principality, the most important trade route passed through Tighina along the line of the settlements of Khotin-Dorohoi, Botoshany, Khirlau, Iasi-Tyagyanyakyach. Already from here the goods went to Belgorod and further to the Crimea. In addition to the walking route, there was also a water route, no less important, along the Dniester River, which brought considerable income to the Tyagin customs.

Some scholars could misinterpret the term "gatehouse", "guard" as a fortress, drawing from this the conclusion that there was a fortified Moldavian fortress in this place. Has she been to this place? Not everything is clear...

The interests and interference of the neighboring states of Moldova - Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, i.e. countries with different socio-cultural and economic potential, as well as the constant pressure of the Tatars, apparently did not allow the Moldavian rulers to build a full-fledged fortress on the site of a convenient crossing near Tighina. Also, most likely, there was simply not enough manpower and means, and most importantly, the sense to maintain and restore the constantly destroyed fortifications.

In addition, whether the rulers of Moldova controlled this territory in full is a big question. The Tatar influence, as well as the very presence of the Tatars, has not disappeared here. On the map of the Moldavian Principality of the times of Stefan the Great, i.e. at the very peak of the power of the state, not far from Tighina, there were Tatar settlements, mainly on the left bank of the Dniester River, i.e. territory that could not be controlled by any of the named states - part of the so-called Wild Field. The only owners of this territory were the Edisan Tatars, who controlled a vast territory from the Black Sea to the Dniester along the Tigina-Orhei line and from whose constant raids the Moldavians had to defend themselves. There are known facts of the complete devastation of entire regions of the principality by the Tatars, but there is not a single confirmation of the attacks of the Tatars on Tigina. Attacks from Tigina - yes, but the Tatars did not touch the settlement itself, which indicates the involvement of the settlement in the economic and political system, including the Tatars.