Author: Irina Vilkova (1972-2020) Head of the Archival and Historical Department of the Internal Affairs Directorate of Bendery, 2011

FOR REFERENCE: AIO was established in 2008 for the economic and museum-excursion services of the Military Necropolis and the Bendery Fortress, as part of the Public Relations and Information Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the PMR. On December 31, 2013, by order of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, G. Kuzmichev was liquidated, the functions of the AIO, as unusual for the PMR Department of Internal Affairs, were transferred to the State Unitary Enterprise IVMK "Bendery Fortress" to civilian specialists.

Preparing materials about prisoners of war, especially about captured soldiers and officers of the Soviet army during World War II, is quite difficult, even for researchers who have access to central archives and direct documentary sources. It's no secret that the soldiers and officers of the Soviet army who were taken prisoner, as well as citizens of the USSR from among the civilian population, driven away to "join" the so-called "great German civilization" and who first went through all the horrors of slavery, and then , after the exhaustion of physical and moral strength, thrown out to die in concentration camps, the attitude in the homeland was, to put it mildly, negative. Millions of people, who already experienced unthinkable torments and survived only by a miracle, were considered traitors and traitors in advance. What caused such an attitude is difficult to answer objectively; say, it was a vivid manifestation of the state system of that time.

Naturally, all documents on this topic (captivity and post-war repatriation) were classified, many are classified even now. For Pridnestrovian prospectors, the task of investigating this issue is even more complicated, first of all, by the fact that all the archives from the cities of Tiraspol and Bendery either died during the war, or, after 1953, were taken out for centralized storage. Some of these documents ended up in Moscow, some are stored in the archives of the Republic of Moldova, and it is difficult to say where it is more difficult to get access to these documents.

The main sources for research on any topic are, first of all, written and material sources. First of all, this is, of course, archival information. They are the most reliable and objective evidence, on the basis of which it is possible to carry out a full analysis and draw conclusions. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, these sources are practically closed to us. The second source is the periodicals of the Second World War and post-war years. This source is more accessible, but it cannot be considered objective, since it was prepared with an eye on the propaganda of those years, and it is extremely difficult to assess its reliability. There remains a third source - the memories of eyewitnesses. In many ways, they are subjective, plus the age of the witnesses and the number of years that have passed since those times should be taken into account.

But if you work with the memories of not fifty or ten people, but with a much larger number, and also strictly filter out discrepancies, emotions, rumors and gossip of those times, leaving only those facts that are confirmed by the testimony of several witnesses independently of each other, then you can get enough an objective picture of what happened in Bendery in the period 1941-1945, including with prisoners of war. I had to go down this path - the names and addresses of residents of Bendery born in 1935 and older were chosen in the social guardianship authorities. There were over four thousand of them. Through a preliminary survey, persons who lived in the specified period of time in Bendery were identified. These people were interviewed in person and on record. From their memories, a picture of those distant years was formed, further refined by available documentary sources. Talking with these people and writing down their memories, it is as if you are immersed in that time and understand how valuable material can be collected from the words of eyewitnesses of the events of that time. The brightest and most interesting memories are used as illustrative material in this work.

Historical digression: the fate of Bender in the twentieth century is fundamentally different from the fate of Tiraspol. The current capital of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic immediately became part of the Soviet Union. The border ran along the Dniester and Bendery, which in the 19th century was part of the Russian Empire, after the First World War became part of the Romanian and capitalist Bessarabia. Even the old Russian military cemetery, on which the Bendery Necropolis Military Historical Memorial Complex is now erected, was called the Heroes Cemetery or Dragaina din Tigina at that time.

Here is the first interview of N.P. Ivashchenko, a resident of the city of Bendery.

“Every year, on July 8, on the Day of Heroes, the Romanian official authorities, citizens, schoolchildren and high school students, with flowers in their hands, came to this cemetery, where something like a mourning meeting was held and flowers were laid on the graves of Romanian heroes ... All the time of the occupation / 1918 -1940 / in the Bendery fortress, an infantry regiment of the Romanian royal army called "Zeche vietor" was constantly stationed. The soldiers of this regiment, who were dying or dying, were buried on the territory of the Bendery necropolis ... The Bendery necropolis at that time had a much larger area, was fenced, and quite well maintained. Burials in the necropolis were differentiated according to the social status of the buried: most of the burials were simple graves with crosses, some of them were abandoned. Only rich people could afford to put a monument on the grave, and there were few monuments. I only remember a few graves that had large white pieces of marble on them, it was expensive. But the Romanians laid flowers at these monuments, which means that the monuments were Romanian. Romanians hated Russians and did not look after their graves too much. We didn’t even know that Russian soldiers, and even more so generals, were buried in the cemetery.”

In addition, the Romanian authorities took care of the military fortification of the city. A chain of five well-fortified bunkers was built in the area of the current Kitskansky Lane, on the territory then called the Plavni suburb. There were other fortifications, which is not surprising - the border was very close. After the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Soviet power is established in Bendery. Not for long.

“After Bendery retreated to the USSR, Russian troops blew up these pillboxes. When the Romanians returned here in 1941, they restored these fortifications.”

“In the early morning of June 22, 1941, German-Romanian troops rushed to the Soviet bank of the Prut River, trying to capture strongholds of border outposts, as well as highway and railway bridges. Enemy aviation bombarded Chisinau, Balti, Cahul, crossings across the Dniester, including near the city of Bendery, a number of railway stations.. Bombs fell on the city itself.

“When I was little, my parents and I moved for a long time to the city of Galati (Romania), due to the fact that my father was transferred to work at a factory. Our family was prosperous, had valuable things. They returned to Bender shortly before the start of the Great Patriotic War, when Soviet power was already in the city. On Sunday, June 22, 1941, my father left for work in the morning. On the same day, the city began to bomb. At that time we lived in our own house on the street. Marosheshty. Father, returning from work, said that the war had begun. He was drafted into the Soviet army and died at the front in 1945. Our family remained in the occupation. Mother was then pregnant, brother was born in 1942, died in 1945..

“On Sunday, June 22, I went to see friends at Balka, through fields and a railway crossing. When I was walking, I suddenly saw planes flying from Tiraspol in the sky. The planes flew very low, they were clearly visible. There were Soviet soldiers at the railway crossing then. They only had rifles as weapons. When bombs started falling from the planes, they started yelling at me: “Where are you going, lie down!”. And pushed me to the ground. And they themselves began to shoot from rifles at the planes and, apparently, they hit some, because several planes fell in the area of the Russian airfield, where the Leninsky microdistrict now stands. The bombing was strong, but I was not very scared. When the bombing stopped, I ran to my friends, and we went to watch how the downed German planes burned out on the ground.

The city resisted the capture as best it could. From June 22 to July 23, with continuous bombing, there were battles. But then the Benders could not survive. “On July 21, 1941, under the pressure of superior enemy forces, the last units of the Red Army left the city, retreating beyond the Dniester. During the withdrawal, their railway bridge and other objects were blown up by our sappers, and on July 23, Bendery was occupied by the German-Romanian fascist troops.

Bendery was taken by the united German-Romanian troops, but the Germans did not linger here - they almost immediately handed over the city to the Romanians and moved on. The Romanian authorities quickly regained their positions here, lost in 1940. And their attitude towards the population in Bendery was somewhat different on their part than, for example, towards the population of Tiraspol - the city was “their own”, habitual. “The urban economy under Romanian rule was quickly rebuilt on the old rails of capitalist relations. People worked in their workshops either for their masters or served in state institutions. The Romanian authorities did not oppress the indigenous inhabitants of the city, or rather, treated them no worse than before 1940. Romanian military units were located in the city.”

“Romanians patrolled the city from nine in the evening until six in the morning, and if the light was on in any house at that time, the patrol would go there and beat the owners for violating the blackout requirements.” “The criminal situation in the city was prosperous, no one was raped, robbed, or touched. The property was not expropriated. Private initiative flourished in the city, there were no state outlets at all, there were only private shops. The Romanians also tried not to touch the local population, punished (sometimes very cruelly) only the delinquent inhabitants. But Russians in general, and prisoners in particular, were hated.”

“From the summer of 1941, Soviet prisoners of war appeared in Bendery, who, as far as I know, were kept in the Bendery fortress at night, and during the day they were used for various jobs in different parts of the city.”

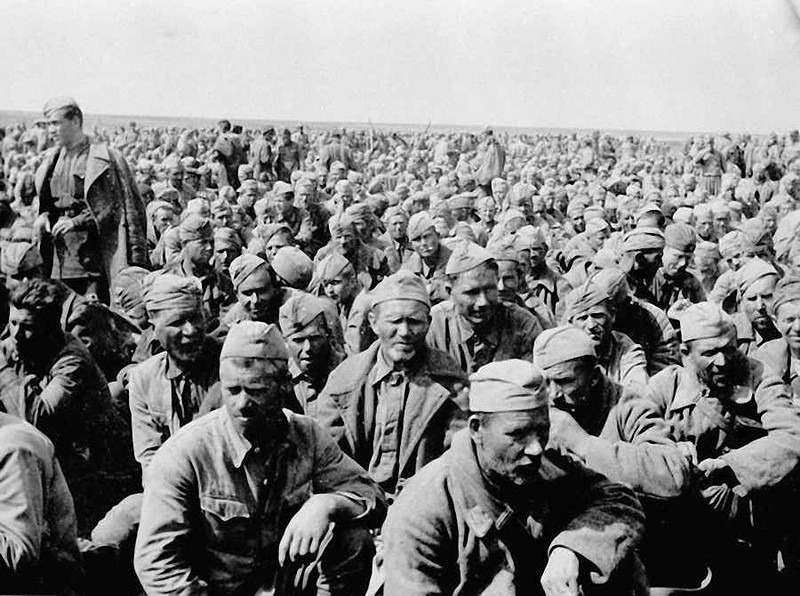

In the period 1941-1944. in Bendery there were several camps in which prisoners of war of the Soviet army were kept. The very first camp was, apparently, a storage and transit camp. It was located in the area of the current shipyard, where then there was an open field. Most of the field was fenced with barbed wire, behind which the camp was located. On the same territory were the buildings of repair shops, in which it was possible to hide in case of bad weather. There were no other buildings, including those similar to the kitchen, in the camp. The prisoners of war held in this camp spent almost all their time outdoors. They were dressed in Soviet military uniforms, some were wounded, and they were wearing bandages and dressings that no one changed.

It is difficult to establish the exact number of prisoners of war held in this camp, but, according to eyewitnesses, there were about five thousand of them. It was strictly forbidden to communicate with these prisoners of war. The camp was guarded by the Romanian military. Guard dogs were also used in protection. The townspeople who knew about this camp went to him on Sundays - visiting the camp was not welcome on weekdays. “That was capitalism. And with him there was no time to walk and wander on weekdays - everyone worked. They went out somewhere, no matter what business, only on Sunday. I went there with my parents and also with women I know. There were quite a few of us." Citizens visited the camp for prisoners of war with a dual purpose - to feed the prisoners and find out something about their loved ones who fought in the Soviet army. Has anyone seen or heard anything? But it was not always possible to talk with the prisoners - it depended on the shift of escorts and guards on duty. Sometimes they were allowed to talk, and sometimes they could fire at them for talking with prisoners. They did not shoot at people, but over their heads, but this measure of intimidation was quite effective. Sometimes it was forbidden even to approach the camp and pass food, but for what reason is unknown.

“Most often, when we came, the Romanian sentries watched us, but did not say anything. So, it was possible to go to the fence and give food. And sometimes they started yelling at us and didn't let us approach the camp. We obeyed. Those who lived under the Romanians knew very well what discipline and punishment were. Why sometimes they were not allowed to approach the camp, I don’t know, maybe their superiors checked, or maybe one of the prisoners of war escaped.

Residents of nearby houses prepared hot food for the prisoners - cereals, borscht, soups. Those who lived farther away brought pies, boiled potatoes, bread, lard. Food was passed through a barbed wire fence. This temporary camp lasted until November 1941. With the onset of cold weather, the camp was liquidated. It was not possible to establish where the prisoners of war were transferred from it. None of the eyewitnesses of those events confirms the facts of the execution of prisoners of war. Most often, prisoners of war died from wounds, lack of medical care, overwork, hunger and cold. But there were executions in the city itself. Although the Romanians considered Bendery to be “their” city, and the attitude towards the population was much milder than in other settlements of the Transnistria governorate and the Bessarabian governorate, all prohibitions and restrictions applied to Bendery residents (for example, to gather in groups, discuss political events and news from the front, speak Russian, etc.). And no one was going to spare the Jews of Bendery. All Jews who did not have time to evacuate from the city were subjected to registration and eviction; some were shot on the spot - in 1944, after the liberation of the city, in the moat of the Bendery fortress (opposite the monument to the 55th Podolsk Infantry Regiment), dozens of burial places of executed Jews, including children and adolescents, were discovered. Now a memorial sign has been erected at the site of this execution. The rest of the Jews were taken to the Dubossary ghetto, where about 20,000 people died. It is already known that 58 people, including women and children, were shot in the Jewish ditch immediately after the city was occupied in August 1941.

In 1941-1942, several permanent prisoner of war camps were organized in Bendery. It was possible to accurately establish the location, the approximate number of prisoners, manners and customs in three cases. The first permanent prisoner of war camp was located on the current Kavriago Street, opposite the building of the Bendery Private Guard. This camp was small, with a capacity of up to a hundred people. The territory was not fenced, there was little security. The prisoners of war held there lived in barracks on the territory, moved freely, went out into the city in groups of five to ten people, accompanied by one or two escorts from among the Romanian military personnel. The townspeople brought their clothes, soap, hygiene products to the prisoners. In those days when such “humanitarian” aid arrived at the camp, the Romanians took the prisoners to the Dniester River in groups of 10 people. There the prisoners bathed and washed their clothes. Some of the prisoners were still wearing the military uniform of the Soviet army, but the majority had already changed into civilian clothes from among the clothes that the townspeople brought.

The prisoners were fed very poorly in this camp, some eyewitnesses claim that they were practically not fed, because about twice a week the prisoners in a group of five people took large pots in the camp and went around the city to ask for food. They went into the houses of the townspeople and people shared with them whoever they could. At the same time, the Romanian guards who accompanied a group of prisoners did not enter the yards and houses, but hid behind the bushes so that they could not be seen.

The prisoners were taken to work every day. In particular, prisoners of war from this camp built a road from the city cemetery (now Suvorov St., 120) to the place where the city meat-packing plant is now located (Industrialnaya St.).

“The stone for the construction was mined at ... the old Jewish cemetery. On the site of this cemetery is now located AGSK-2 on the street. Sadovaya and Avtokolonna-2836. Groups of prisoners under escort came to the cemetery, smashed tombstones and other stones into rubble there. This rubble then went to the construction of the road.

The second camp was located in the area of the current industrial zone, approximately on the site that is now occupied by the Oil Extraction Plant (Kommunisticheskaya St. - Echina St.). At that time, this large urban area was simply called Camp Field. This POW camp had no permanent buildings, only a few temporary tents. The prisoners actually lived in the open air, regardless of weather conditions. The territory of the camp was not fenced, only a trench was dug from the side of the Dniester River. The prisoners were guarded by Romanian military personnel, as well as Russians who went over to their side and became policemen. There was little security. The prisoners were used in a variety of urban and agricultural work. The number of prisoners of war exceeded three hundred. They were fed very poorly.

“We owned gardens and farm animals in the village of Farladany (actually a suburb of Bendery). I remember that once we returned from there and brought fruits and vegetables, grapes to Bendery. Mom told us to turn closer to the POW camp to give them some food. We wanted to give the prisoners grapes, but the prisoners refused the berries and asked for bread.” The prisoners also had a great shortage of tobacco. They asked him even more than bread. The children of the townspeople took tobacco from their parents and carried it to the camp to the prisoners. The territory of this camp was patrolled, but the prisoners tried to help the townspeople a little, in particular, in the matter of preparing firewood.

“The Romanians patrolled the territory of the camp and the works being carried out, but the prisoners of war allowed us to pick up and take with us the brushwood that remained from cutting down the trees. Trunks of trees after felling were cleared of branches and taken away to the city somewhere. When a Romanian patrol passed by and turned its back on a group of prisoners of war, they told us: "Get quick / brushwood / and run." If the Romanians saw that we were taking brushwood, they drove us out, but did not shoot.”

The third permanent camp was located on the territory of the Bendery fortress. It was not possible to establish exactly where and in what buildings of the fortress the prisoners of war were kept. Most likely, on the territory of the former pontoon battalion in the buildings of the flank casemate caponiers (buildings with earthen roofs). But eyewitnesses claim that they heard about the location of the camp in the fortress directly from the prisoners of war themselves. Moreover, there is reason to believe that Camp No. 2, located on the Camp Field, was, so to speak, a summer branch of the Bendery fortress. The prisoners of war in the camp in the Bendery fortress were deprived of medical care, and they were constantly taken out to work. Particularly hard work was cargo handling at the railway station. The prisoners involved in this work were strictly guarded, on the railway facilities there were towers with armed Romanian soldiers. Trains with various cargoes constantly arrived at the station. Unauthorized persons were not allowed into this territory, and they shot immediately and without warning. So, Viktor Pavlovich Zubchenko, who at that time was 11 years old, once tried to get closer to the working prisoners of war and throw them a few beets from his parent's garden, located next to the railway tracks. The sentry who noticed his “maneuvers” immediately and without warning opened fire on the teenager. Fortunately, the bullets did not hit him and, after the fear he experienced, he no longer risked approaching the prisoners of war.

The lack of proper nutrition and medical care, exploitation in hard work led to high mortality among prisoners of war. The dead prisoners were buried at the old Borisov cemetery, the one where the Bendery Necropolis Military Historical Memorial Complex is now located. The dead and dead prisoners of war were buried almost in the same place as the Romanian military, but the funeral procedure, of course, was radically different. If the Romanian military personnel were buried in coffins, with musical accompaniment and proper military honors, as well as with a funeral service by a priest, then the prisoners were buried two or three bodies in one grave. At first, the bodies were wrapped in old blankets, and only a year later they began to be buried in wooden coffins. Above these mass graves, the same reinforced concrete crosses were placed as for the Romanian military personnel, but the inscriptions on the cross read: “PRIZIONER RUS” (RUSSIAN PRISONER) - without surnames or any other identifying data. Some of the crosses with such half-erased inscriptions were discovered during the clearing of the cemetery in 2007. How many Soviet prisoners of war are buried at the Borisov cemetery is unknown. From the recollections of eyewitnesses, it was possible to establish a more or less accurate figure of 150 funerals, but, of course, this is not all. Therefore, at the Military Historical Complex for the Soviet prisoners of war buried there, one common monument without surnames was erected.

As it was possible to establish thanks to the lists of the deceased servicemen of the Romanian army, which is currently being systematized, in the city of Bender in the period 1941-1944, mainly infantry and infantry regiments were stationed; also in the Bendery fortress there were parts of artillery regiments, the 3rd aviation flotilla, border units, etc.

In August 1944, after a long and stubborn resistance, the troops of the Soviet army approached Bendery. A general flight began in the city. Mostly Romanian troops fled. At the same time, they managed to rob city apartments and houses, taking with them everything that was of at least some value. Trucks and cars, carts and wagons, foot columns left for the West. The defense of the city was taken over by German units from among the units of the army "Southern Ukraine". German troops resisted to the last. The last days before the liberation of the city, everything around turned into hell. The city was continuously bombed by Soviet and American bombers. There are almost no surviving houses and buildings in the city. Corpses lay on the streets, which, with the next explosions of bombs and projectiles, "flew up above the wires." Before leaving the city, the Germans and Romanians dispersed the sick from typhoid barracks and a typhus epidemic came to the city: typhus, typhoid, relapsing typhus mowed down the few surviving citizens. The city is practically dead. The restoration of the city after the war is a separate and glorious page of heroism, well reflected in the materials of the city museum of local lore. And the prisoners of war were removed from the city in advance. It was not possible to establish where they were evacuated, what happened to them next. After the front left Bender further to the West, a camp was set up in the city, now for foreign prisoners of war from among the military personnel of the Nazi army.

According to the archives of the NKVD in the Republic of Moldova, fragmentary information from which fell into the hands, a large number of prisoners of war were Magyars (Hungarians), whose country fought on the side of Nazi Germany. The camp had the serial number "NKVD-No. 104". From a survey of residents of the city of Bender, no one could name his exact location. Presumably, he was in the Bendery fortress, on the site of the former camp of Soviet prisoners of war or at the entrance to the village of Protyagailovka, the city of Bendery. One of the residents remembers that in 1944, German prisoners were brought into the city “... German prisoners, after the liberation of Bendery, were brought to the city one day. They were led in a huge column from the side of the village. Farladany, we form five people in a row. The first hundred meters of the column were made up of senior officers, who walked in uniform and with numerous awards. There were so many officers and there were so many awards, so many that the ringing of their awards could be heard very far away. There were so many prisoners that they were led from 8 am to 4 pm, all in the same formation. The prisoners were escorted by soldiers on horseback. These prisoners were taken to the territory of the Bendery fortress.” As mentioned above, it is reliably known that Hungarian prisoners of war were also kept in the camp. In the course of working on this material, the Hungarian authorities, with whom it was possible to contact, suggested that this camp did not contain captured soldiers and officers, but the male population sent from the cities of Hungary liberated from the Nazis to forced labor to restore the cities of the Soviet Union . But this assumption cannot be considered justified, because of the 318 Hungarian prisoners of war who died in the city of Bender in 1945 in camp No. 104, all of them, according to the available list, had military ranks from private to chief officer. Moreover, many eyewitnesses claim that almost all the prisoners, including the Hungarians, were dressed in military uniforms. Here it is necessary to make a small digression. Many respondents, when giving interviews, by and large did not classify the prisoners according to nationality, usually calling everyone Germans. It is reliably known that in the city in the NKVD camps of the city of Bender, in addition to Hungarians and Germans, Romanians were also kept, and in Tiraspol, Japanese were also exotic for our places. Therefore, later in the interview, the term "Germans" is replaced by the term "prisoners".

As eyewitnesses explain in their interviews, the conditions of detention in the Bendery prison camps were quite tolerable, if not good. This is confirmed by many documents.

“The prisoners /1944-1945/ were not offended, not beaten, they were fed very well at the expense of the Red Cross. It is noteworthy that during the distribution of food to the prisoners, no one thought to feed their escorts. In addition to prisoners of war, convicts were also kept in these NKVD camps. I remember a former city judge and prosecutor who also worked on construction sites with the prisoners. One day, while escorting the prisoners to work, I wanted to pick grapes for myself in a mined vineyard (I knew where the mines were planted). The prisoners asked to collect grapes for them. I collected a whole backpack of grapes, for which the prisoners treated me to chocolate - the first chocolate in my life.

From the Order of the NKVD No. 00683 of April 9, 1945, it becomes clear that in addition to food and things from the Red Cross, quite tolerable food standards were established for foreign prisoners of war. And this is in a war-torn country. So, for non-working prisoners, only the daily bread ration was 600 grams. Cereals (70 grams), meat and fish (50 and 3 grams), lard and vegetable oil (3 and 10 grams), tomato puree (10 grams), potatoes, cabbage, carrots (300, 100 and 30 gr.), greens, cucumbers, tea, peppers, bay leaves, tobacco and laundry soap, etc. How many residents of the city of Bendery in 1945 had 600 grams of bread and 300 potatoes a day?

The prisoners were used to restore and build the destroyed objects of the city. “The prisoners built, basically, five objects around the city. As far as I remember, they were building a cinema named after Gorky, restoring the park opposite the cinema; the third object is store No. 27 near the Bendery-1 railway station; the building of the railway station and the old railway bridge. At that time, on the instructions of the military commissariat, I acted as an escort to the prisoners and accompanied them to work every day.

Studying documents after 1946, no information about prisoners of war in the city of Bendery was found. There are a lot of sources on this topic in the archives of the NKVD, which is currently stored in the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Moldova, but access there for researchers is still closed. As sources are identified that expand the field of knowledge on this issue, it will be possible to prepare new publications on the issue of prisoners of war in the city of Bendery, an issue that has never been carefully studied until now.

It is not known what other secrets the Bendery land holds, but thanks to researchers, local historians, just inquisitive and talented people, these secrets are gradually being revealed to us.

“Now death and time have reconciled everyone,” such a wise saying comes to mind when you are on the territory of the Military Historical Memorial Complex. Here, in addition to the graves of Russian soldiers and officers, there are memorial plates to the French, Swedes, Romanians, Ukrainian Cossacks Pylyp Orlyk and Ivan Mazepa, as well as those who died in the 1992 war. Truly a crossroads of history and destinies.

- Interview with Getmanskaya (Novatskaya) Z.M. 2009. Benders. The materials are stored in the Archival and Historical Department of the Internal Affairs Directorate of the city of Bendery.

- Interview with Ishchenko N.P. 2009. Benders. The materials are stored there.

- Perstnev V.I. /Benders. Fiery bridgeheads of war / Bendery, Polygraphist 2004. p.5.

- Interview with Bachila (Baldescu) M.G. 2009,

- Interview with Brad N.I.

- Perstnev V.I. /Benders. Fiery springboards of war / Bendery, Polgirapist 2004. pp. 34-37.

- Interview with Getmanskaya (Novatskaya) Z.M.

- Interview with Vasiliev V.K.

- Interview Zubchenko V.P.

- Name from the 19th century. The divisions of the Russian Imperial Army held summer exercises in this place, hence the name.

- Interview with Ishchenko N.P.

- Pages of the Military Necropolis of old Bendery. Issue #1

- List of prisoners of war who died in the NKVD camp No. 104 in Bendery in 1945. TsGAO MSSR. Archive of the NKVD in the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Moldova.